We Must Do Better, Acquire Excellent MIGS Skills

Nils Loewen, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

When glaucoma treatment was mocked by a colleague during my PhD studies at Mayo as 'basic plumbing', I was upset about how this contrasted with our increased understanding of the delicate outflow tract physiology. But the criticism was right! We now know from well-designed RCTs that, even in highly experienced hands and when performed as primary procedures, urgent postoperative interventions are needed in an astonishing 74% of trabeculectomy procedures and 27% of glaucoma drainage devices, while vision threatening complications occur with an additive probability of 77% and 58%, respectively.1

When a new generation of intricately micro-engineered prototypes of devices, the iStent and the Trabectome, could be explored in anterior segment perfusion culture,2 we all shared the excitement of bypassing or even eliminating the primary pathophysiology of POAG while maintaining the remainder of the natural outflow route. Recently, the development of new minimally invasive (MIGS) or non-penetrating glaucoma surgeries has dramatically accelerated: there are now several such procedures. By now, even a second generation for some of these surgeries has arrived. With increased expectations, the quality of validating studies has improved, as well.

Glaucoma specialists still not versed in MIGS should recall the numbers above and ask whether the average IOP of 14.4 mmHg for tubes (trabeculectomies not significantly different) is enough to justify them as a primary procedure.3 A poll at the recent Hawaiian Eye indicated that barely 3% of attendees would agree to a traditional surgery for themselves instead of trying a MIGS first, regardless of the glaucoma stage. While RCTs provide sound conclusions, one cannot dismiss the large body of prospective data that some of the more mature MIGS have accumulated by now. For instance, the TVT study compared 107 tubes with 105 trabeculectomies. In comparison, more than 50,000 Trabectome cases have been documented worldwide to date and more than 5,000 have been recorded in detail and followed long-term via a repository that is made available to researchers. Phaco-Trabectome IOPs at five years were 15.2 mmHg,4 only marginally higher than in the TVT study. The iStent with same-session phacoemulsification achieved 16.8 mmHg at five years.5 Directly comparing IOPs reported for MIGS and traditional surgeries is problematic, of course, because MIGS patients often do not need a profoundly lower IOP but instead want to reduce drops and improve vision.

Yet bypassing a trabecular meshwork with advanced disease or very high pressures may produce a larger IOP drop, while bypassing a mild trabecular meshwork (TM) resistance may create the illusion that this surgery is less effective in general and not appropriate for advanced glaucoma. Our own experience with a modified, large ablation arc technique in 200 consecutive Trabectome surgeries for patients who would normally have received a tube or trab (including failed trabeculectomies and tubes in both open- and closed-angle glaucomas), suggests that an average 28% IOP reduction with a final IOP of less than 18 mmHg can be achieved in 81%, less than 15 mmHg in 52% and less than 12 mmHg in 27% of patients (personal communication, submitted).

The most serious complication of MIGS is a temporary, more than ten mmHg IOP increase during the early postoperative phase that can occur in, e.g., 3-10% of Trabectome5 and 2% of iStent patients.6 Early postoperative, transient hyphema is characteristic for all canal surgeries and more common to procedures that generate access to many outflow segments by ablating trabecular meshwork over a large arc allowing direct reflux into the anterior chamber and less common to procedures that provided focal entry into a few clock hours of the naturally discontinuous and septated Schlemm's canal. Differences between classic glaucoma surgery and MIGS are reminiscent of those between phacoemulsification and extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) and so compelling that no RCTs have compared the two (and only a few compared phaco and ECCE). Similar to ECCE, trabeculectomies are low tech, appropriate for advanced disease, feature a large incision but produce more complications and have variable outcomes. In contrast, both phaco and MIGS are high tech, more appropriate for moderate disease status, can be performed through a small incision, are safe and produce more predictable outcomes because they are more standardized. MIGS requires a mind- and skill set that is more akin to a retinal membrane peel and the learning curve is very considerable before good results can be achieved. Instead of creating > 2 mm flaps, punching half-millimeter scleral holes and placing sutures, a lacy and translucent tissue has to be carefully engaged and removed within a space of 50 to 300 micron without pushing outward ruining the outflow channels.

No interventional cardiologist would perform a stenting procedure without angiography. Similarly, glaucoma surgeons have to learn to use high resolution SDOCT of the outflow system7 in order to determine the best location for stent positions and meshwork ablation to guarantee that sufficiently large collector channels exist and that two stents are placed into separate drainage segments to maximize efficacy. This will also answer questions in TM ablation: does descemetization of the angle, outer wall trauma with subsequent proliferation or a reactive attenuation of collector channels exist? Could, e.g., intracameral dexamethasone at conclusion of surgery reduce ablation trauma - a strategy that we deploy - or would topical vasodilators, such as Rho-kinase inhibitors, counteract a hypothesized collector attenuation? Discovering resistance mechanisms downstream of the TM could bring about a paradigm shift and enable new treatment modalities.

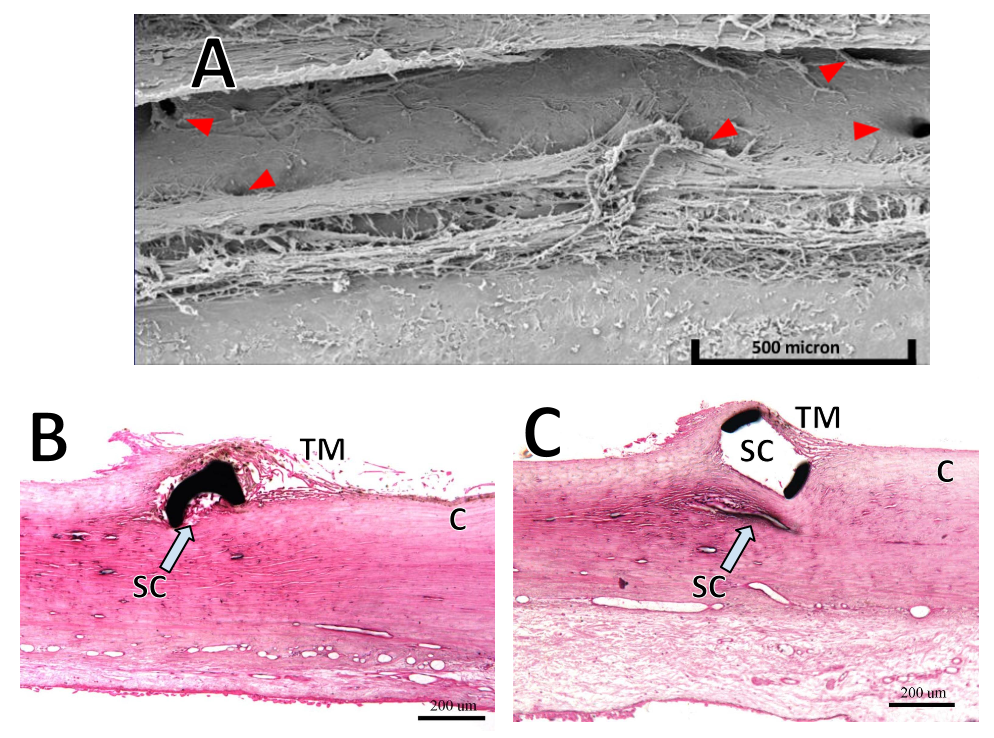

Problems of tubes and trabeculectomies are present to some degree in MIGS: stents and scaffolds in Schlemm's canal can occlude intakes, compress adjacent structures and incite variable tissue reaction (see Fig. 1), migrate or get lost in as many as 10% of patients, while microshunts that bypass the outflow tract internally (suprachoroidal shunts) or externally may encounter fibrosis similar to their larger cousins. Too high-power Trabectome ablation may not leave a stump of viable TM as a barrier to proliferation of adjacent tissues and hypotony can cause hyphema. Perhaps genetic reprogramming or replacing the TM will avoid these problems? There is still much too learn.

Figure 1. Challenges encountered by MIGS. (A) Electron microscopic view of unroofed Schlemm's canal. Red arrows indicate collector channel orifices that are close to the anterior and posterior ablation lip (courtesy of Neomedix Inc.). B) Section through microstent in Schlemm's canal (SC) shows that the lumen may be partially occluded. C) Scaffold device that distends SC but may compress adjacent collector channels (CC; B) and C) courtesy of Invantis Inc.).

References

- Gedde SJ, Herndon LW, Brandt JD, Budenz DL, Feuer WJ, Schiffman JC. Postoperative complications in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) study during five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol USA 2012; 804-814 e801.

- Johnson DH, Tschumper RC. Human trabecular meshwork organ culture. A new method. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1987; 28: 945-953.

- Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, Feuer WJ, Herndon LW, Brandt JD, Budenz DL. Treatment outcomes in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) study after five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol 2012; 153(5): 789-803.

- Mosaed S, Dustin L, Minckler DS. Comparative outcomes between newer and older surgeries for glaucoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2009; 107: 127-133.

- Ting JL, Damji KF, Stiles MC, Trabectome Study G. Ab interno trabeculectomy: outcomes in exfoliation versus primary open-angle glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg 2012; 38: 315-323.

- Arriola-Villalobos P, Martinez-de-la-Casa JM, Diaz-Valle D, Fernandez-Perez C, Garcia-Sanchez J, Garcia-Feijoo J. Combined iStent trabecular micro-bypass stent implantation and phacoemulsification for coexistent open-angle glaucoma and cataract: a long-term study. Br J Ophthalmol 2012; 96: 645-649.

- Francis AW, Kagemann L, Wollstein G, et al. Morphometric Analysis of Aqueous Humor Outflow Structures with Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012; 53: 5198-5207.